When it comes to the translation of Scripture, the King James Version set an ideal that every literal translation since has sought to emulate. Still, in order to have an accurate understanding of history, the KJV must be viewed within the broader context of English translation of Scripture. The translators of the KJV say it best:

“Zeale to promote the common good, whether it be by deuising any thing our selues, or reuising that which hath bene laboured by others, deserueth certainly much respect and esteeme, but yet findeth but cold intertainment in the world. It is welcommed with suspicion in stead of loue, and with emulation [jealous rivalry] in stead of thankes…

As nothing is begun and perfited [perfected] at the same time, and the later thoughts are thought to be the wiser; so, if we building vpon their foundation that went before vs, and being holpen by their labours, doe endeuour to make that better which they left so good; no man, we are sure, hath cause to mislike vs.1

The translators actually spent most of their eleven-page preface arguing that it was essential for believers to continually revise and improve translations in English.

Wee neuer thought from the beginning, that we should neede to make a new Translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one… but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principall good one.”2

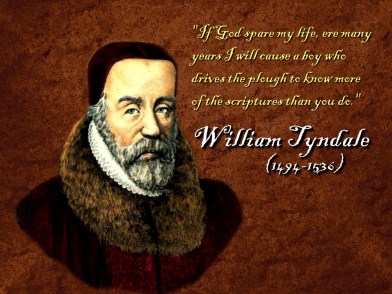

The “many good ones” refers to Wyclif’s translation,3 Tyndale’s translation, Coverdale’s Bible, Matthew’s Bible, the Great Bible, the Geneva Bible, and the Bishop’s Bible among others. The KJV translators understood that they continued in a long heritage of English Bible translation which could be traced back to Wyclif’s work c. 1382 and for some portions, even before that.

This tradition was continued in the revisions to the KJV in the years after 1611. Indeed, in the years from 1611 to 1644, there were 182 editions of the KJV published, each containing revisions.4 Other significant revisions occurred in 1701, 1762, and 1769.5 The 1769 edition is the closest to what we know today as the King James Version.

This tradition was continued in the revisions to the KJV in the years after 1611. Indeed, in the years from 1611 to 1644, there were 182 editions of the KJV published, each containing revisions.4 Other significant revisions occurred in 1701, 1762, and 1769.5 The 1769 edition is the closest to what we know today as the King James Version.

Translations, such as the New King James Version of 1982 and the 21st Century King James Version, have overtly attempted to update and revise earlier editions of the KJV.

Many other translations have seen themselves in the line of tradition in which the translators of the 1611 edition saw themselves. A brief perusal of each of the following translations demonstrates that each made explicit reference to the 1611 edition at the very beginning of their preface: The English Revised Version/American Standard Version (RV/ASV), the Revised Standard Version (RSV), the New American Standard Bible (NASB), and most recently the English Standard Version (ESV).

See how the translators of the ESV of 2001 place their translation:

“The English Standard Version (ESV) stands in the classic mainstream of English Bible translations over the past half-millennium. The fountainhead of that stream was William Tyndale’s New Testament of 1526; marking its course were the King James Version of 1611 (KJV), the English Revised Version of 1885 (RV), the American Standard Version of 1901 (ASV), and the Revised Standard Version of 1952 and 1971 (RSV). In that stream, faithfulness to the text and vigorous pursuit of accuracy were combined with simplicity, beauty, and dignity of expression. Our goal has been to carry forward this legacy for a new century.”6

Within this “classic mainstream,” the King James Version stands as a towering monument to the grace of God in revealing himself to man. May we never lose sight of the necessity of making God’s Word available to God’s people in their common language so they can learn to live it and love it and rejoice in the God who gave it.

What do you do to help in this sacred work?

Grace to you.

1 Smith, Myles. “The Translators to the Reader.” The Holy Bible, King James Version, 1611 Edition. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2003. The original spellings have been maintained and definitions have been given in brackets for words that are no longer in common usage. The passages differ from the original 1611 edition only in the font in which they are presented.

2 Ibid.

3 Though Wyclif’s translation was not directly from the original languages and precedes modern English, I include it here because it arguably influenced Tyndale’s work in some ways, however minor.

4 Beale, David. A Pictorial History of Our English Bible. Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 1982, p. 46.

5 Williams, James, & Shaylor, Randolph, eds. From the Mind of God to the Mind of Man: A Layman’s Guide to How We Got Our Bible. Belfast: Ambassador-Emerald International, 1999, p. 159ff.

6 The Translation Oversight Committee. The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Wheaton: Crossway Bibles, 2001, p. vii.

About Jason Harris

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Our church this week is putting together 28,000 KJV Bibles for every high school student in the Solomen Islands. It’s amazing to think that 400 years ago, people were doing the same thing… Mind you, I think our job is easier than back then… =)

[NOTE: Links have been deleted. Disagreement is completely welcome, but commenters are asked to make their own arguments rather than linking to others work or cutting and pasting. ed.]

Hi, I am from Melbourne.

Please find a completely different Illuminated Understanding of the origins and POLITICAL purposes of the Bible via this reference. Political purposes which were intended to consolidate the worldly power of the church fathers who fabricated the Bible.

[Link deleted]

Plus related references on the self-serving nature of the mommy-daddy religion that you promote.

[Link deleted]

[Link deleted]