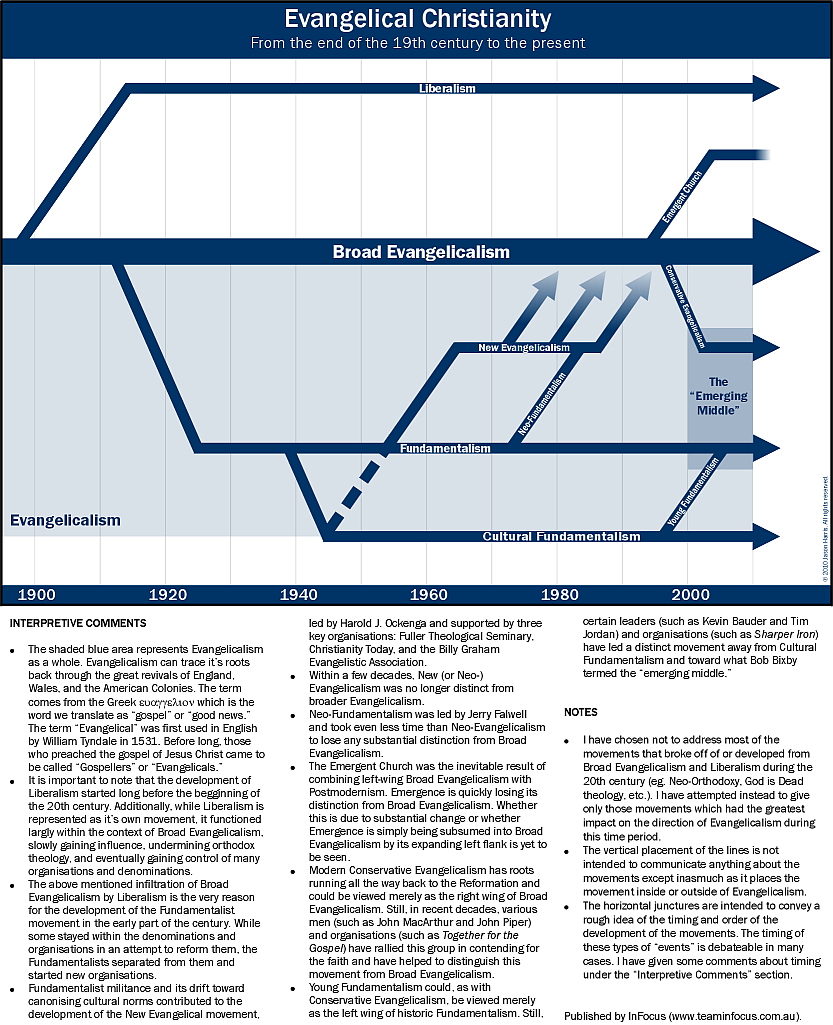

Recently, a friend was asking me about modern church history. By the time I’d finished explaining bits and pieces of it, I had the broad scheme of Evangelical Christianity over the last century—at least my take on it—scribbled on a scrap of paper.

Discerning that there could be value in graphing the history of modern Evangelical Christianity, I set to work.

The graph

Below is what I came up with. I present it here for two reasons:

1) I feel that it has some educational value for those who are interested in learning in this area.

2) I would like feedback on it.

You can enlarge it by clicking on the image and then clicking it again.

Areas of interest

What I find particularly interesting is trying to tie the events of the last decade into the picture of the 20th century. Have I given a fair picture of the composition of the “emerging middle”?

I’m also particularly interested in feedback on whether I’ve been fair and accurate in my approach to Cultural Fundamentalism.

Yet another question is whether I’ve been fair in my definition of Evangelicalism (as represented in the large blue shaded area).

Feedback

I’m aware of the dangers of trying to encapsulate more than a century of Evangelical history into a single graph. Doing so involves the collation of thousands of variables and historical events using broad simplifications and interpretations.

That’s why I would appreciate feedback on this. Please point out any errors of fact or ways in which you feel the ideas could be more effectively charted.

Grace to you.

About Jason Harris

6 Comments

Comments are closed.

Cool graph. Could you explain a bit more on what is “Cultural Fundamentalism” as well as the “emerging middle”?

Yes, just realised I have not addressed cultural Fundamentalism in much depth in the comments.

Cultural Fundamentalism is that element within Fundamentalism that tended to canonise cultural norms. Certain “standards” on issues like movies, dress, drinking, etc. were no longer viewed as areas for the application of biblical principles, but instead, were viewed as biblical in and of themselves. This focus on externals coincided with (resulted in?) a degradation of the theology of the movement until it bore little resemblance to historic Fundamentalism (aka historic Evangelical, orthodox theology).

The “emerging middle” is a term coined by Bob Bixby in this post. Probably the best way to understand what it refers to is to read Bob’s original post.

Thanks for the questions.

As a summary and introduction into that area of modern Church History, it’s not bad, although as you say it is lacking in detail.

I would see the divergence of Fundamentalism and Liberalism as more of a fork in the road, with the New-Evangelicals moving more toward a middle ground. Your graph can give the impression that churches within the Broad Evangelical stream are historically orthodox, since they are traced back to before Fundamentalism began. So I would get rid of the Broad stream and make the New and Neo’s move into the Broad part and the Emergent church come out of that. Does that make sense?(probably not)

By the way, is Cultural Fundamentalism a nice way to say Legalism?

Thanks for your comments Steve.

I viewed this issue exactly as your second paragraph described it until recent years. Your view is also the view commonly taught in several Fundamentalist schools.

The reason I adjusted my view is because I came to the view that Nonconformists (those who stood against Liberalism, but did not come out of the denominations/organisations as the Separatists did) could not always be labelled as Fundamentalists.

It’s as if they chose not to separate along with the Fundamentalists but we gave them honourary membership in the movement for believing what we believed even though they didn’t necessarily want to identify with Fundamentalism. That view seems presumptuous on the part of the Fundamentalists and so I adjusted my thinking to allow that some people stayed in the denominations/organisations that were riddled with Liberalism and fought for Reformation.

I feel that those people have a claim to being what they were before Liberalism invaded—namely, Evangelicals.

Again, I realise that many have taken your view so I’m interested in hearing arguments against my view.

As far as Cultural Fundamentalism, I suspect all of these movements have a solid claim to the Legalist title at a heart level. Still, I know what you’re saying. I do think this stream of Fundamentalism tended toward actually teaching overt legalism, but the label is designed to communicate more than that.

Cultural Fundamentalism tends to insert cultural norms in place of Scripture itself. Indicators of this include diminished emphasis on expositional preaching, a refusal to part with traditional translations, the proliferation of eisegetical preaching, an inconsistent hermeneutic, anti-intellectualism, etc. These types of things undermined the authority of Scripture and left little but culture/tradition to fill the void.

Thanks for the comment. I appreciate your perspective.

I see your point about people staying in liberal denominations. I thought the graph pictured movements, organisations and denominations rather than individuals, so that is where I misinterpreted it, although your Interpretive comments do mention denominations, organisations and movements rather than individual people.

What about the graph portraying a fork when Fundamentalists and Liberals split, and another fork when Fundamentalists and Evangelicals split shortly after. This would show the Fundamentalist separation from Evangelical Christianity. There would be a similar fork on the other side where Liberals diverge from less liberal folk, which would form a shaded middle area of Evangelicalsm with its conservative and liberal elements joined together.

Good point with the Cultural Fundamentalists, it is a better term than legalists, not only less confronting but as you say it encompasses some other issues as well.

Sorry for the delayed response Steve. I’ve been busy avoiding other things. =P

You are correct that the graph does represent movements, not individuals. I apologise for failing to communicate my point effectively.

Perhaps to illustrate. The Southern Baptist Convention is I believe the largest Christian denomination in the world. While we could say that Liberalism gained a significant hold of a significant number of churches and schools within the SBC, I do not believe it would be accurate to say that the SBC left Evangelicalism and became part of the Liberal movement. Rather I think that it remained part of the Evangelical movement but was deeply infiltrated by Liberalism. In the last two decades we’ve seen Conservatives Evangelicals bring reformation to the denomination to the point where you argue a case for classifying the SBC as Conservative Evangelical—part of the “emerging middle.”

I think the fork-in-the-road approach is too simplistic. I’ll try to explain based on the SBC illustration.

Take a Pastor Bob in the SBC in the early mid 20th century. Liberalism is gaining huge ground in the denomination. The Fundamentalists are writing books and thundering across the platforms that it is time to leave the SBC. While Pastor Bob is very concerned for the SBC and firmly stands for the Evangel (gospel), he isn’t quite prepared to lead his church out of the SBC just because other churches in the convention are getting tripped up by Liberalism.

Now the fork-in-the-road approach seems to imply that Pastor Bob, by refusing to take a right down the Fundamentalism road, has automatically taken a left down the Liberalism road. I just don’t see that as a fair picture. Pastor Bob would be incensed at the idea that he had gone down the Liberalism road. He repudiates everything Liberalism stands for. Yet he has not chosen to identify with the Fundamentalist movement either explicitly or implicitly. What do we say happened to Pastor Bob? I’d suggest that nothing happened. He’s an Evangelical just like he always was.

And to clarify that I’m not talking about just an individual or a church, Pastor Bob represents thousands of pastors in thousands of churches, within and without the SBC, that did not become Liberal, but neither became Fundamentalist. Those, I would suggest, comprise the Broad Evangelical movement of the 20th century.

Regarding your second paragraph, I don’t view it as Liberalism and Fundamentalism splitting. I view it as Fundamentalism leaving Evangelicalism because Evangelicalism wasn’t militant/separatist enough for the Fundamentalists at the time. Again, with New Evangelicalism, I view it as the New Evangelicals that left Fundamentalism. Fundamentalism didn’t really change. The NE’s left the movement and branched off. Let me just stress this point. The Neo-Evangelicals started as Fundamentalists and chose to leave to forge a new approach… a return to the old Evangelicalism so to speak… they were not Evangelicals. They were exFundamentalists who eventually became Evangelicals by virtue of the fact that they had no significant distinction, and I suspect no significant desire to be distinct.

To illustrate this point, Billy Graham attended Fundamentalist Bob Jones University for a time and held campaigns on the BJU campus early on. It was Graham that took a new direction in that case, not the Fundamentalists. Graham followed a ministry model that was decidedly Neo-Evangelical and openly identified with that movement. Of course once he had, the Fundamentalists were happy to give him a solid kick on the way out the door…

Anyway, that is the rationale behind my approach. These issues are very difficult to quantify and I realise it could be argued in many different directions.

Thanks again for challenging my thinking and please hit me with any additional issues that come to mind.